“In a place without words, there is only a strong embrace.”

A note:

If you find it offensive to read about the lives and realities of Israeli Jews, as if this is somehow an affront to civilian suffering in Gaza or a negation of the Occupation, this writing and likely much of what I may be processing in weeks and perhaps months (years?!) to come may not be for you. I’m not here to change anyone’s minds or to compare suffering.

If you are a person who holds multiplicity, who recognizes that this war is not one-sided, and who appreciates that lifting up Jewish and Israeli experiences is valid and deeply needed – particularly in the face of vast misinformation, shallow and one-dimensional thinking, and ignorance about this region – please read on. And thank you for being there.

Friday greetings,

I don’t know where to start.

I landed early on Sunday morning after nearly two weeks in Israel, nine days of which I spent immersed in learning at the Rabbinic Torah Seminar (RTS) at the Shalom Hartman Institute in Jerusalem. The days and evenings were dense and rich with classes, lectures, book talks, and small group discussions, all circling around and diving into the theme of “Israel Tomorrow.” After sleeping for 14 hours Sunday night, I returned to a full life this week, time with M.J., Aviva, Pearl, and my parents, calls with clients, and a snaking to-do list that will, in all likelihood, never see completion. I have reams of notes and readings I’m eager to revisit and sift through. I hope to distill even a fraction of the brilliance of the Hartman faculty and the nearly 200 North American rabbis (plus a handful of folks like me who are not rabbis) with whom I had the privilege of studying and connecting.

In a word (or more precisely, a single, hyphenated adjective), it was life-changing.

Or maybe more accurately, it affirmed what I have known to be true in my kishkes for a very long time: This world and this work is where I belong.

My desire to pursue the rabbinate is clearer than ever. It feels like a need, the thing in this life that will not let me go. I am trying to quiet the noise in my head around how that can possibly happen from a logistical/practical/financial point of view. As I would tell my kids, stay close to the vision and the intention, and fill in those questions one step at a time.

When I work with writers, or people who don’t consider themselves writers but wish to write, one of the most common things I hear is that they don’t know where to start.

Often, when they tell me more about this struggle, they proceed to say all kinds of things that I’ll see on paper in my mind’s eye as I listen. Sometimes, I’ll invite a pause and say, “Write that down! That’s where you start!”

“The impediment to action advances action. What stands in the way becomes the way.”

~ Marcus Aurelius

Moishik, it wasn’t boring.

Daphna is 80-something, a dear friend and dance colleague of my mom’s. I spent time with her and her darling Moshe, who at 84 is long retired from his career as a psychiatrist. They live in the apartment where he grew up, in the building his paternal grandfather and one of his sons bought after leaving their chocolate factory in Warsaw in the 1930s and subsequently bringing over much of his family. The high-ceilinged rooms are teeming with heirlooms and books, family photos and DVDs, and an oft-used record player.

Life wasn’t easy, but we are lucky. Moshik, aren’t we lucky?

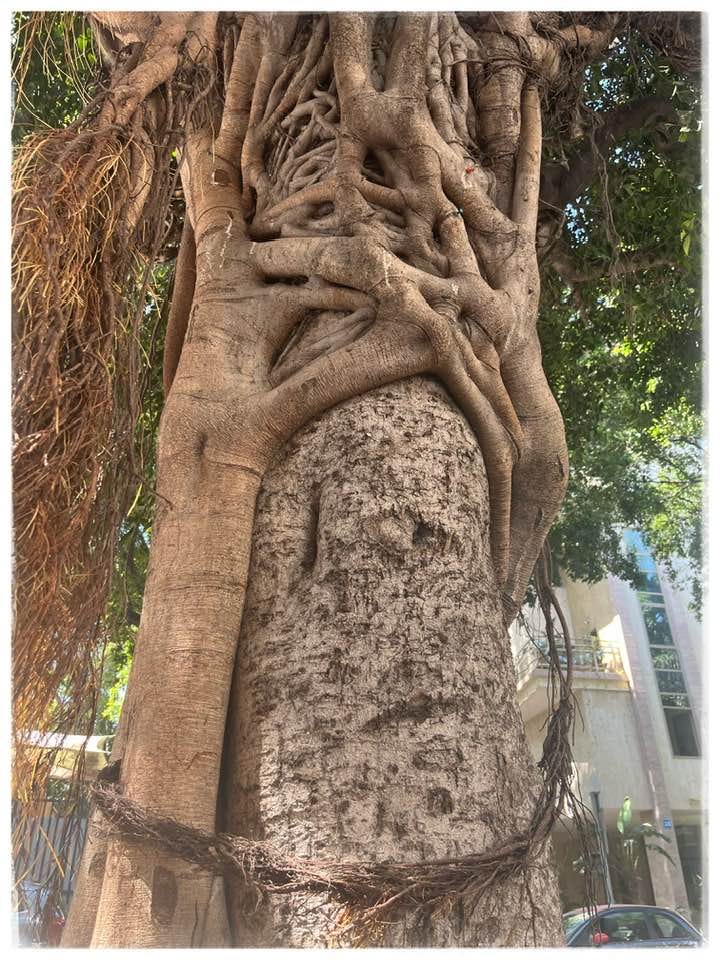

I steeped in their personal histories and hospitality as we wandered the neighborhood where Daphna greeted neighbors and Moshe pointed out each building, what decade it was from, and the ficus trees that line the dense residential streets in that part of the city with their dramatic roots, like so many limbs, like hearts on their sleeves.

Oy oy oy.

A week before, I had lunch with Einya on Emek Refaim in Jerusalem, another of my mom’s long-time dance soulmates. She told me about her kids and grandchildren, one of whom has proclaimed their mission in life to make Chaim, Einya’s husband of many decades, happy. The closeness of family was so palpable.

Then there was the next day, a Friday afternoon visit to Vivian’s apartment, the 90-something-year-old mother of one of my dearest American friends. We had, of course, heard a lot about each other over close to a quarter-century. I brought a huge bouquet, which she placed in water on the dining room table next to the Shabbat candles waiting for sundown, and I soaked in the stories she shared of her life and work.

And then there was Saturday after havdalah, when one of my new rabbi friends and I went in search of the protest we knew was happening that night. We thought it was near Netanyahu’s residence, where there is a tent with information about the hostages, but the area was practically desolate. In the tent, we met a young man whose name means “lost” in Hebrew; he also wanted to find the protest so we joined forces and made our way to the Knesset (parliament) building where sure enough, hundreds of people had gathered, many of whom had just spent four days walking from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem. Chants of “Bring them home now!” and posters of hostages, protestors young and old, drums and bullhorns and rainbow flags and pink t-shirts all conjured the predominant mood of much of the country: An agonized, angry, and desperate demand of the government to prioritize the return of the remaining hostages over everything else. The young man we met was half-Israeli and half-Italian, working towards a Master’s in Switzerland where he has felt completely ostracized by his fellow “far, far left” friends and peers. No Israelis allowed at a party. Swastika graffiti in campus bathrooms. And, he said, a sense of emptiness in returning home to Israel. He lit up upon spotting friends at the heart of the protest, running over and sharing the biggest hugs.

I thought about the young people in the U.S. who identify as anti-Zionists. So many times on this trip, I wished they could teleport into the three-dimensionality of anguish and devotion and real-ness and diversity and despair and exhaustion and depth.

Then there was a squeezed-in coffee date with a woman who has been close friends with one of my sisters for 30+ years, an American who married an Israeli and now has three kids, one of whom is in the army. We fell into fast conversation about our lives and could have talked all day had she not had groceries to pick up for Shabbat dinner and had I not had to be in the Hartman beit midrash at 8:30am.

Later in my trip, I met up with another friend, Tanya, on the beach in Tel Aviv. We talked about writing and life while her nine-year old daughter jumped the tiny waves. Tanya who began writing in my online groups eight and a half years ago, whose family made aliyah from the former Soviet Union when she was a child, who is afraid to go on trips here and there this summer because anything could happen at any time – another Hamas terror attack on the ground, a drone that sneaks past the iron dome from Hezbollah or the Houthis, as happened in Tel Aviv on my first night there, a quarter-mile from where I slept.

And on my last day, sitting in the living room of an academic colleague of my father who shared so openly and vulnerably about how protesting the government in 2023 was like a second full-time job, and now here they are still at it, every Saturday night in Hostage Square, lifting up the names and stories of those still being held in captivity, screaming on the deaf ears of self-serving leaders.

A flu, sciatica, a mystery skin rash, a slipped disc – I couldn’t help but wonder if it was a coincidence that many of the Israelis I visited with have been experiencing physical ailments and conditions. Stress, as we know, manifests in the body.

The shopkeepers who thanked me for coming. The young people whose lives are defined by service and loss and uncertainty, who never asked for any of this. The activists who have devoted their lives to coexistence.

How does one not feel hopeless in such a place, in such a time?

And yet I did not feel hopeless.

I felt energized, challenged, enlivened, aware and alert, sad, grateful, conflicted, curious, at times overwhelmed, receptive, humbled, and most of all, so very present.

Being in Israel, and I realize this might sound very strange, was a relief. Not because anything makes sense or is simple, but in a funny way, because life happens in the presence of the impossible. Like the motley crew of people of every age who show up on Tuesday nights for folk dancing at the Cosell Center, some in their schmatas and others dressed to the nines, grabbing joy and connection even when nothing is ok. The musicians on Ben Yehuda Street and the young woman who spontaneously danced so un-self-consciously to an electric violin, her eyes closed, limbs like tree branches. The multi-generational families of evacuees from both the north and south, living in hotels indefinitely as their homes are not safe to return to amid ongoing attacks. The crash of religious and secular, the clash of what looks to the naked eye like normalcy against the backdrop of a country fighting for itself against forces both external and internal. The fact that wearing a “Bring Them Home” dog tag or a Star of David doesn’t stand out. The hostage posters everywhere, the anti-Bibi graffiti. To be unapologetically Jewish, without feeling like one has to explain oneself, assure others that of course we are not monsters – I cannot really put into words the space this opens up in one’s being. My being.

Sitting across the table from Daphna: You seem like you’re from here. My mother would say it must be from a past life.

That would explain why I dreamed this place long before I set foot there. That would explain why I knew, even before I arrived this time, that it would be so hard to leave again.

Back home, I completed the trip report for one of the grants I’d applied to. Some of my responses repeat the stream-of-consciousness sharing above, but I’ll extend them here nonetheless.

Did your experience meet your expectations? Explain in detail.

The experience met and exceeded my expectations, so much so that I don't even know where to begin. From the moment I set foot in the airport to the last conversation I had with a seatmate on the plane on the way home, this trip brought so much depth and three-dimensionality to this moment in Israel. Learning from brilliant faculty and connecting with 250 North American rabbis (and a small number of non-clergy like myself) deeply affirmed my commitment to serving the Jewish people and Israel.What did you do and where did you visit while in Israel?

Though I had planned to participate in the Community Leadership Program, I ended up being invited instead to attend the 9-day Rabbinic Torah Seminar at the Shalom Hartman Institute in Jerusalem, the theme of which this year was "Israel Tomorrow". Classes, hevruta, book talks, and live podcast recordings covered a multiple of topics, including "Crashing: Jewish Peoplehood After October 7" with Yehuda Kurtzer, "Poetry in the Wake of October 7 in Conversation with Sacred Texts" with Dr. Rachel Korazim, "A Nation That Dwells Apart" with Tal Becker, talks by Sharon Brous and Yitz Greenberg, "Antisemitism, Anti-Zionism, Anti-Zionist Jews" with Yossi Klein Halevi, "Preaching Through Times of Crisis" with Elana Stein-Hain, "Palestinian Israeli Identity and Shared Society Post-October 7" with Rana Fahoum, "Responding to Devastation" and "Turning to the Shechinah to Give Voice to the People Israel" with Melila Hellner-Eshed, "If I Forget You, Jerusalem: An Ancient Trail of Ascent and Hope" with Tamar Elad-Applebaum and Rani Jaeger, and "Reclaiming Our Moral Voice" with Donniel Hartman. We also went on a tiyul (field trip) to Otef Aza (Gaza Envelope) where we visited Kibbutz Kfar Aza and the Nova Festival site. I went to Nava Tehila's Kabbalat Shabbat service, visited the Old City/kotel, attended a protest at the Knesset, and visited Hostage Square in Tel Aviv. I met with Israelis, friends and colleagues, in their homes, and listened to stories of how they are coping. I went folk dancing and hiking with Keren Rhodes, the executive director of the Jewish Community of Amherst who happened to be doing a program at Yad Vashem during the same time period. I did a lot of walking in Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, taking in the sights, sounds, and smells of life happening, the graffiti and hostage posters everywhere, the rhythms of life amidst war and uncertainty and shattered hearts and hope running out of time.What was the most rewarding part of your trip to Israel?

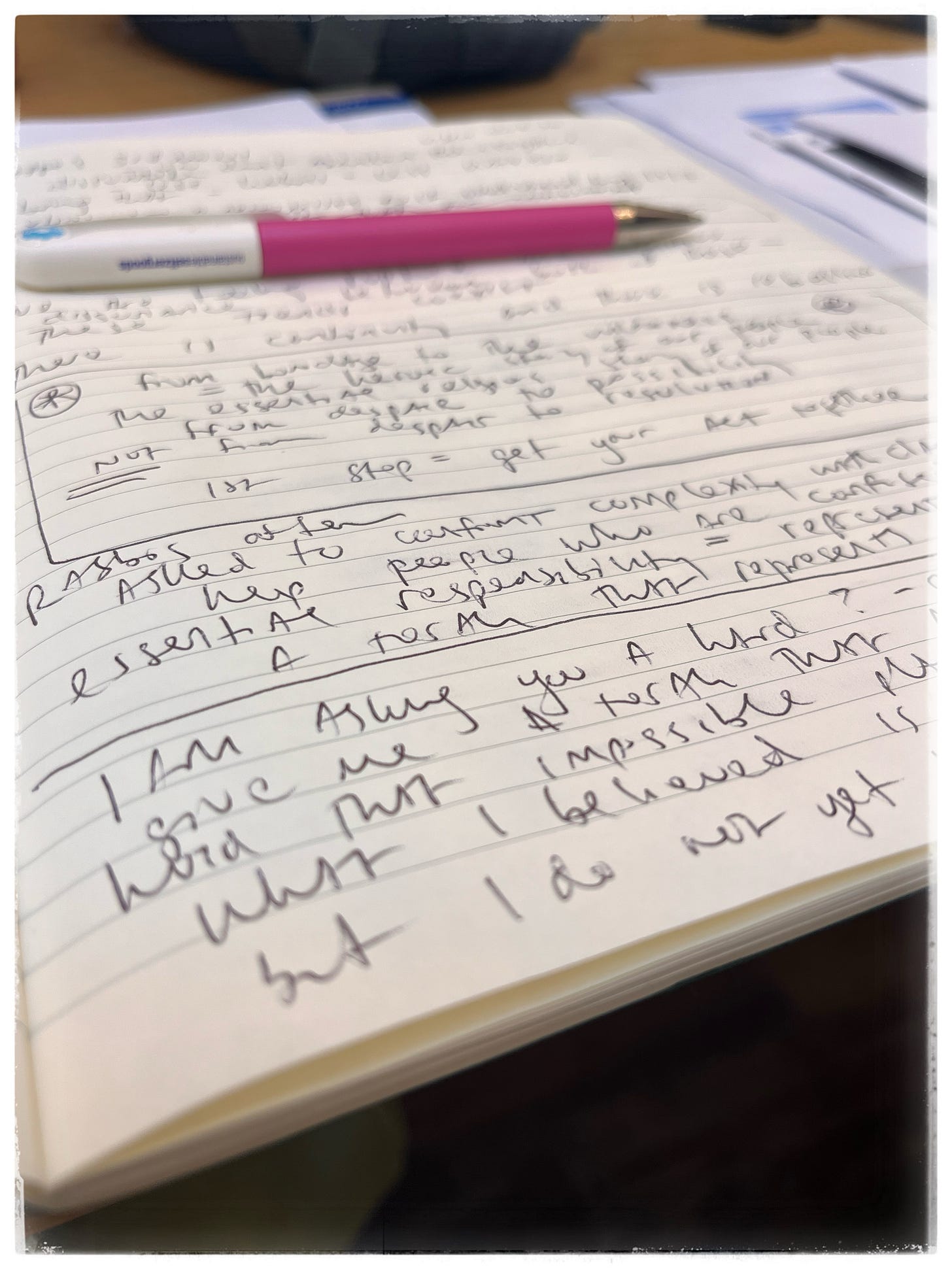

Being able to breathe. Being surrounded by people who love Israel and who know that to love Israel is to struggle with Israel. So much deep learning. I am eager to go through my notes and begin to absorb and process even a fraction of what is in those pages. Forming new connections and friendships with American and Israeli rabbis. Meeting people I've known on Facebook for many years in person for the first time. Crying during services. Bearing witness – to the evacuee families living in my hotel, to the few people who have returned to their homes in the south, to the Nova massacre site. These memories will be seared into me. Experiencing the juxtaposition of how "life goes on" against the backdrop of so much loss and pain. Listening to Israelis – elders and shopkeepers, academics and spiritual leaders – and their appreciation that we came. Deepening my knowledge about what Liberal Zionism actually means, where it has fallen short and/or is imperiled, and how we can even begin to think about tomorrow under the current conditions. Experiencing the anger and betrayal so many feel. Feeling first-hand how much is at stake. Putting my feet in the sea.

Plucked from my notebook:

We can’t not mourn, yet we can’t only mourn. We have to feel this grief and we also have to somehow move forward. Our apartness also contains a deep celebration of distinctiveness, something that has contributed to our being allies to other marginalized groups yet that many liberal Jews in the West haven’t also applied to ourselves. We prize the universality of our Jewish values, but negate the things that make us “too Jewish.” What might it look like to embrace particularism, without closing our circles so completely that we break the compass of caring not only for ourselves but for all of humanity? Is being a “nation apart” a blessing or a curse? If it’s a curse, how do we overcome it? What is the cost of assimilation? Antisemitism, by definition and in practice over the course of thousands of years and in every civilization where Jews have lived, targets the aspects of Judaism that most separate us from the rest of society. Jews come to represent the qualities society finds most objectionable and loathsome. At the same time, the loudest voices in the room – in Israel – pose a moral embarrassment and a danger to the values and aspirations of Zionism. How big is our tent and who is in it? Where are our red lines and why? How do we make room for necessary criticism when we are so girded and guarded against those who criticism lacks nuance? How do we foster smart conversations and protect cherished relationships from rupture? How do we make room for imagination during such a crisis? Power and powerlessness. Victims and victimizers.

None of this is as simple as it looks or sounds. As Donniel Hartman asked on our last morning, “When is it too early, and when is it too late?”

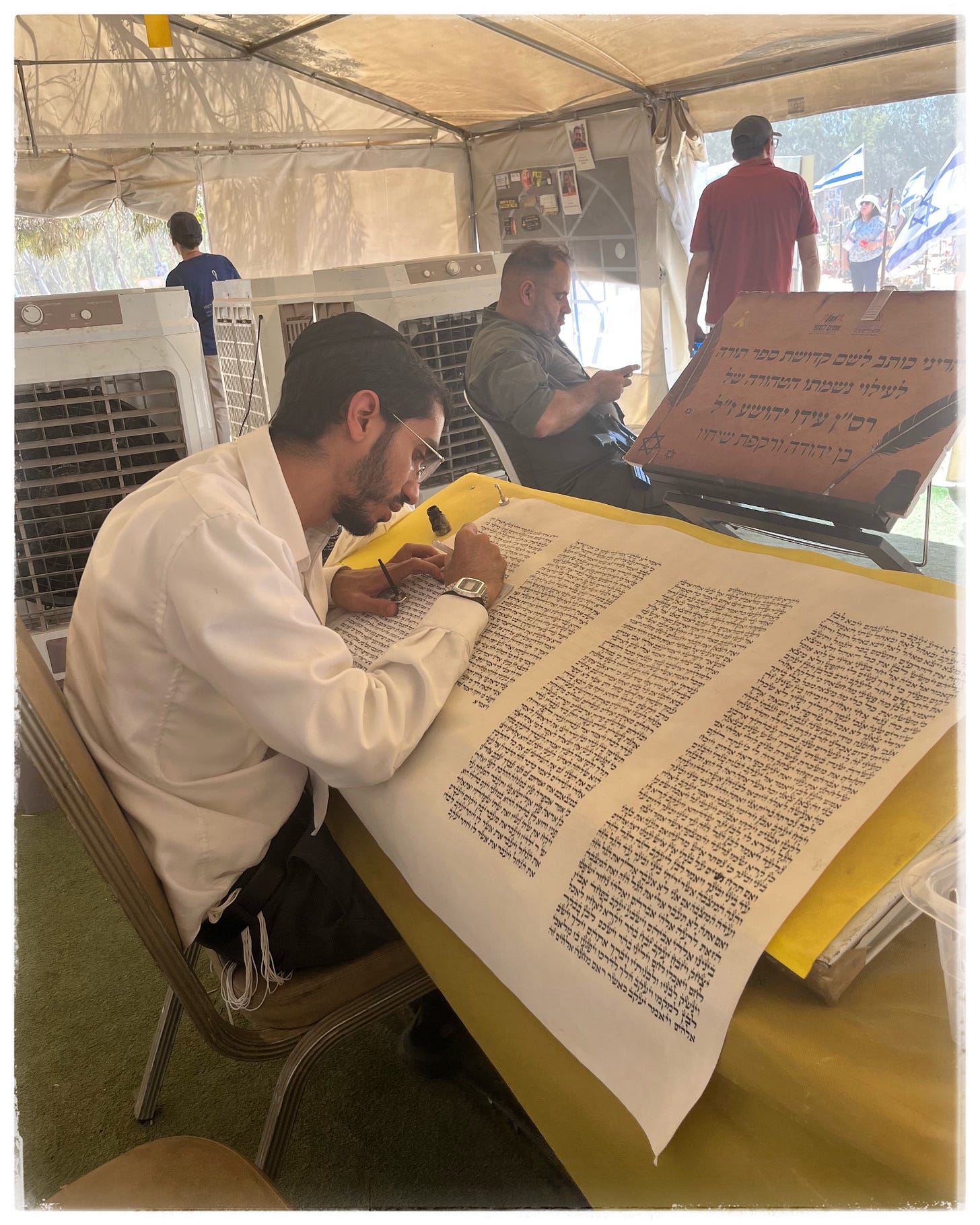

From the abyss to hope. Choosing life. This is the Jewish story, over and over and over, manifest in the scribe writing a new Torah scroll inside a tent at the Nova site, on the grounds of a massacre.

Yehuda Kurtzer spoke of the essential religious story of the Jewish people as the journey from bondage to the wilderness, from despair to possibility. He noted that we never reach resolution.

So much of the tension I’ve experienced since October 7, which I think is indicative of American politics more broadly, is that there is tremendous pressure to express certainty and resolution. To be absolutely sure about who is right and who is wrong. In very different ways, I’ve experienced this pressure both from without and without.

If I carry one thing back with me from this trip, it is this: I am on the journey. We are on the journey. There is no resolution. There is hard-heartedness. There are calls to soften and competing calls to harden. There is so much loss and grief. There is the collapse of some of our most familiar narratives, both personal and collective. There is the need to stand up and stand together. There is no single story and yet there is one body. There is the shechina, dwelling wherever she finds us weeping, connecting, calling out, reminding us we are never alone.

On the way to the south, our wonderful British-Israeli guide, Alexandra, passed out a handout with poems, readings, and prompts for setting our intentions for visiting Kibbutz Kfar Aza and the Nova Festival memorial site.

Here is what I wrote that day:

On the Way to Kibbutz Kfar Aza and the Nova Festival Site

May I stand not around the edges but step in, not only to say I see you but I am here with you, I will tell the world what I learned in this place, the stories of the residents who were there and are there still, the story of the buildings, the safe rooms secured with only the effort of a human body for hours while the air seeped out of the room and the terrorists snacked in the kitchen on the other side of the door among murdered neighbors and loved ones, the land that was attacked, violated, defiled. May my presence today be an offering to the eventual healing, of here, of there, of you, of me, of us, of all, of Am Yisrael, and of the wider world. Amen.

“May You send blessing in our work.” ~ from the Prayer for Safe Travels

The eyes of all who see us see so many things, depending on who is seeing and what they are looking for. There are many who see us as complicit, as enemies of peace, as the very foes this prayer would shield us from. May I open my ears to the sounds – past and present – that I might otherwise silence or shut out. May I not push away pain but honor it and let it change me. May I hear the Common Myna, the wind in the eucalyptus leaves. May I remember that there is no right and no one way to respond or feel, and resist the urge to name the unnameable and understand the unknowable.

After Visiting Kibbutz Kfar Aza and the Nova Festival Site

The experience of October 7 has epicenters, and yesterday I visited two of them. We set an intention on the bus on the way there, as a group, and our guide then encouraged us to consider our own intention. We were not going there to be voyeurs to trauma but to be present as witnesses. By truly listening and seeing, in hopes of understanding something beyond our own experiences, ideas, notions, or opinions.

And, we – the Jewish people – are one body. Blunt trauma to one area of the body emanates outward, leaving no system, no organ, no limb, no dimension unaltered. It’s crucial to hold these concentric circles close to our minds and hearts – those of with more physical and psychological distance from the attacks have a distinct responsibility to hold in the wholeness those without a buffer. It is all of ours, yet as a diaspora Jew I cannot possibly equate my October 7 to that of Shachar, our guide at kibbutz Kfar Aza, or the families of the hostages, or the mothers, fathers, sisters, brothers, grandparents, children, aunts and uncles and cousins and best friends of those murdered at the Nova festival. Bearing witness was — is — a profound, sacred experience.

These words from Shachar – who only began learning English nine months ago – stay with me: “To be a Jew in Israel means to be an optimist. I’m one of the most optimistic men in the world right now because I chose to live here [and come back]... Both sides need a better leader so we can all have a better life.”

Read more about Shachar Shnurman, whose name means “dawn” in Hebrew, in this New York Times article. The flags in the middle photo say “peace.” At the end of our time together, he implored us to go home and talk about those still being held hostage by Hamas.

Democracy is very much at stake in Israel as in the U.S. Extremists, on the right in Israel, and both the right and the left in the United States, threaten to close in on the visions and values so many citizens of both countries hold dear. We don’t have time. And we also have to take the time, take our time, if we are going to get through this with care, which we must. We must.

A Man In His Life

by Yehuda Amichai

A man in his life has no time to have

Time for everything.

He has no room to have room

For every desire. Ecclesiastes was wrong to claim that.

A man has to hate and love all at once,

With the same eyes to cry and to laugh

With the same hands to throw stones

And to gather them,

Make love in war and war in love.

And hate and forgive and remember and forget

And order and confuse and eat and digest

What long history does

In so many years.

A man in his life has no time.

When he loses he seeks

When he finds he forgets

When he forgets he loves

When he loves he begins forgetting.

And his soul is knowing

And very professional,

Only his body remains an amateur

Always. It tries and fumbles.

He doesn’t learn and gets confused,

Drunk and blind in his pleasures and pains.

In autumn, he will die like a fig,

Shriveled, sweet, full of himself.

The leaves dry out on the ground,

And the naked branches point

To the place where there is time for everything.

Shabbat shalom and love,

Jena

I’m always here for multiplicity, hard as it often is to hold.

Thank you for writing this. Thank you for sharing your experience, a brave thing to do. I am really trying to understand what is happening right now, and your perspective gives me insight. I hope we can hold on to our humanity through all of this.