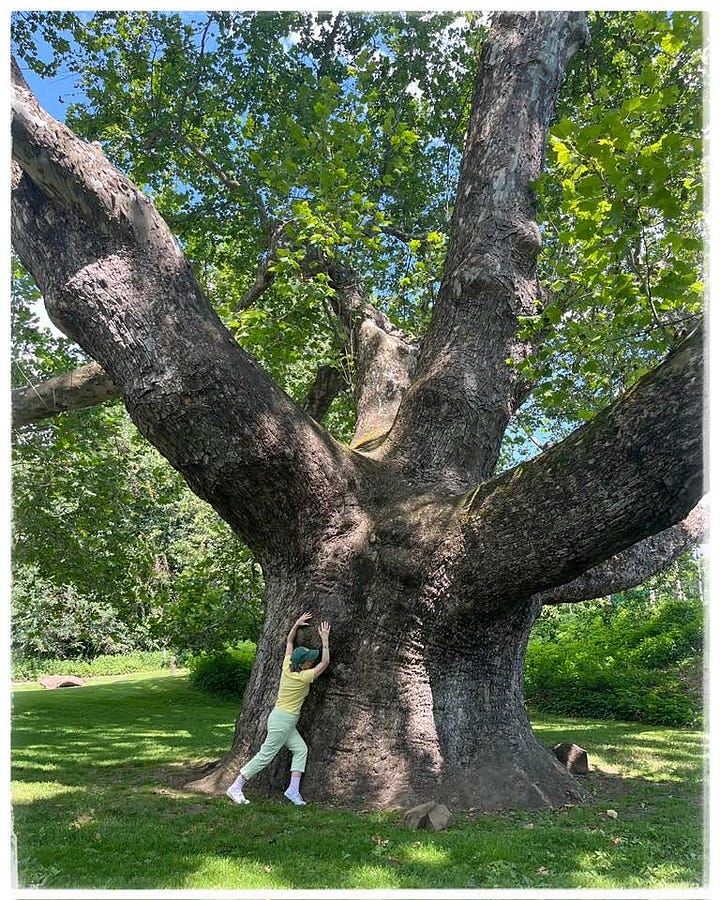

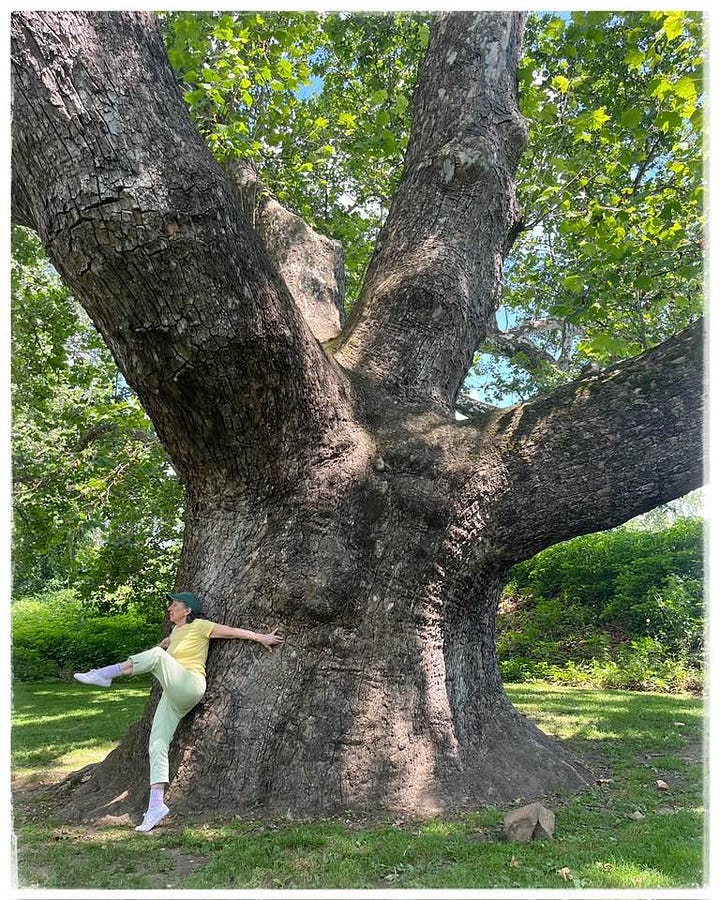

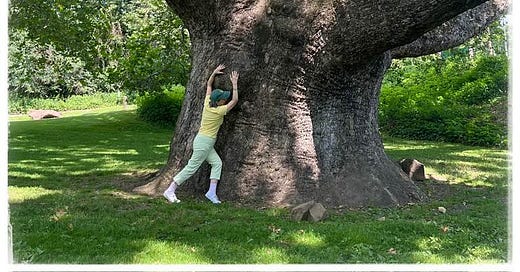

The Pinchot Sycamore, Simsbury, CT

“To write is, in a sense, to try to understand, and so it is always something that happens after the fact, is always a process of sifting through the past, and the results of this, is one is lucky, are permanent marks on a page. But to dance is to make oneself available (for pleasure, for an explosion, for stillness); it only ever takes place in the present––the moment after it happens, dance has already vanished. Dance constantly disappears… The abstract connections it provokes in its audience, of emotion with form, and the excitement from one’s world of feeling and imagination––all of this derives from its vanishing. We have no idea how people danced at the time Genesis was written; how it looked, for example, when David danced before God with all his might. And even if we did, its only way of coming to life again would be in the body of a dancer who is alive now, here to make it immediate for us for a moment before it vanishes again. But writing, whose goal it is to achieve a timeless meaning, has to tell itself a lie about time; in essence, it has to believe in some form of immutability, whihc is why we judge the greatest works of literature to be those that have withstood the test of hundreds, even thousands of years. And this lie that we tell ourselves when we write makes me more and more uneasy.”

~ Nicole Krauss, from the novel “Forest Dark”

Friday greetings,

I’ve read this arresting passage several times this week, including yesterday out loud to my mother, which is when I understood something in a new way, perhaps for the first time. And that was this: Rather than trying to create a permanent record, my writing has always felt in some ways ephemeral to me, like something that is here and then isn’t, just as dancing is for her. (This may explain why I have never been as interested in publishing in a conventional sense as I have been in sharing along the way.)

I write the way she dances, not to preserve things, but to move through things.

There is a fleeting quality to the way I relate to writing, quite the opposite of permanence, as if when I write, I am forever aware that this is here and then it is not here, just like the dance, like the light and shadow, like the morning and evening. And in that very impermanence, there is a steadiness, the reliability of which steadies me, for it is there I find something like wholeness, which is also something like comfort.

Maybe this is why we keep visiting old trees, where she dances, then I write about it.

There is a poem she recalls having danced to called Tree Old Woman. We search and search, and still cannot find the poem. She turns up other poems about old trees and old women, but not this one.

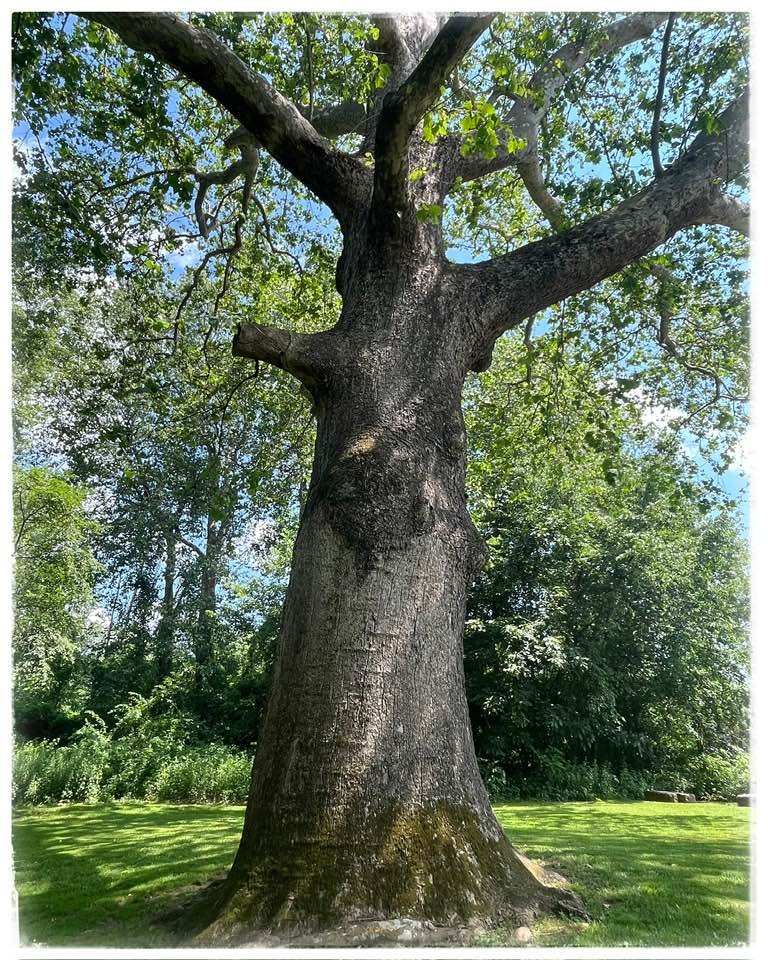

And it occurs to me now: Maybe that is the poem we are writing together, and it vanishes even as we make it, and we have only these pictures and memories, and in time, they will vanish, too. Yet the memory of it all somehow continues, and I cannot tell you how, not at all. It might be in the trees themselves that welcome and witness us together, or in the tiny egg in the perfect nest I found yesterday in the pot I was about to toss out, sad that all of my watering hadn’t saved the flowers from the heat. Or maybe memory lives in the ancient alphabet she sees in the sycamore trunk – oh, it’s like the wisdom of the world in that belly. Or in God, who is in all of this, is all of this, all of this at once, always coming into being and always vanishing, always writing and dancing, always shining and shadowing, always asking us to keep looking, keep moving, keep loving to keep things whole.

A precious surprise

We were eating Indian takeout when our neighbor texted: “Double rainbow!”

Shabbat Shalom and love,

Jena

She moves to keep things whole

The Pinchot Sycamore’s nearby companion (ancient alphabets)

Beautiful! Best yet!